Between the Bindings: Uncovering the Histories of Irish Women Writers

Dr Zoë Van Cauwenberg

Zoë Van Cauwenberg explores some of the Irish women writers and illustrators in the Benjamin Iveagh collection.

During my PhD viva, one of the examiners—partly in jest—remarked that my dissertation had a ‘Lady Morgan–shaped hole.’ For anyone working on early-nineteenth-century Irish literature, this omission is somewhat glaring, as Lady Morgan, born Sydney Owenson, had an almost Sally Rooney like fame in her day. The hole had partially been intentional: my dissertation discussed women’s engagement with Ireland’s and Scotland’s medieval past, while Lady Morgan’s works are mostly set in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Coming to Marsh’s Library enabled me to browse through her extensive oeuvre. I was very excited to handle the physical volumes, leaf through them, feel their weight, and gauge their size in ways that cannot quite be conveyed by digital copies.

In my enthusiasm, I compiled a reading list of forty-five titles. It amounted to close to one hundred books, as most of them consisted of multi-volume works by Lady Morgan and her perhaps even more famous contemporary, Maria Edgeworth. I had to forego much of Edgeworth’s works, as time caught up with me.

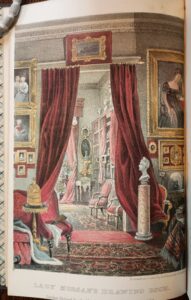

Lady Morgan’s drawing room in Passages from My Autobiography (1859)

I moved from the large green marbled volumes of Lady Morgan’s Italy (1821), a travelogue woven with reflections on history, politics, and art, to her encounter with a giraffe in her travels to Paris as recounted in France in 1829-30, and from there to the pastel pink intimacy of her Passages from My Autobiography (1859). Judging from their pristine condition, they were mostly luxury items made to sit on a shelf, look beautiful, and signal the collector’s interest in Ireland and Irish literary output.

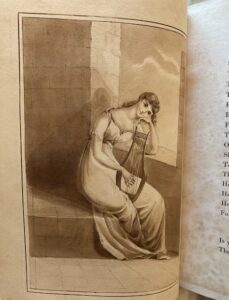

Illustration by Mary Balfour in Walter Scott’s Lay of the Last Minstrel (1803)

That collector was Benjamin Guinness, 3rd Earl of Iveagh. Many of the books I consulted had come from his collection, donated to Marsh’s and still housed in his library in Farmleigh House. Which is why, on a dreary Thursday in May, I wound up rain-soaked on the porch of Ireland’s state house. I got to marvel at the stunning bound tomes and sit in the gorgeous library. There, I stumbled across a most unexpected find: a first edition of Walter Scott’s Lay of the Last Minstrel (1803), lavishly bound and illustrated. The sepia drawings within are unique, commissioned by the book’s original owner Rev. Thomas Vesey Dawson from his sister-in-law, Mary Balfour. A note revealed the copy had once been on loan at the Tate Modern.

Another serendipitous encounter occurred in the pages of Selina Martin’s Summary of Irish History (1847). There, I found a reference to ‘Beaufort’s account of medieval architecture from 1827’. This turned out to be Louisa Catherine Beaufort, the first woman to publish in the Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy. Admittedly a ‘nepo’ baby (her father was a founding member of the Academy) it is nonetheless remarkable that she compiled and illustrated over one hundred pages on pre-Norman monuments in Ireland—a feat I think warrants her recognition as a female antiquarian.

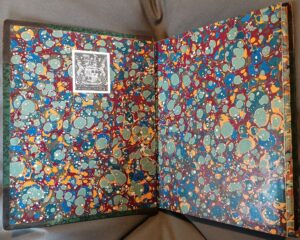

Marbled endpapers on Lady Morgan’s Italy (1821), with Benjamin Iveagh’s bookplate

A planned consultation with Sr. Mary Ursula Young’s A Sketch of Irish History (1815) led me down a small rabbit hole. I wasn’t sure what a history written by a Catholic nun would yield, as most publications of this period were by the hand of the Protestant ruling class, Anglo-Irish Ascendancy. Going through the catechistic question-and-answer history, I came across some bold statements that were anything but friendly toward the English, the British crown, and the Irish Protestant elite.

This book was apparently deemed ‘too monstrous’ and banned from Catholic schools in the 1820s for fear it would predispose young readers to ‘hate’ the Anglo-Irish and British establishment. Who would’ve thought that a radical voice would be hiding within cloistered walls in Cork?

Whether by design or by chance, my time at Marsh’s Library yielded some fascinating stories. The ‘Lady Morgan–shaped hole’ is anything but filled, rather it opened up a space to consider the many voices that helped shape Ireland’s literary and historical culture in the early nineteenth century.

Dr Zoë Van Cauwenberg is a BAEF postdoctoral fellow in Irish Studies at Boston College, where she researches women’s antiquarianism in late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century Ireland.