Marsh’s earliest printed treasures

Sara D’Amico describes what she found among Marsh’s oldest printed books.

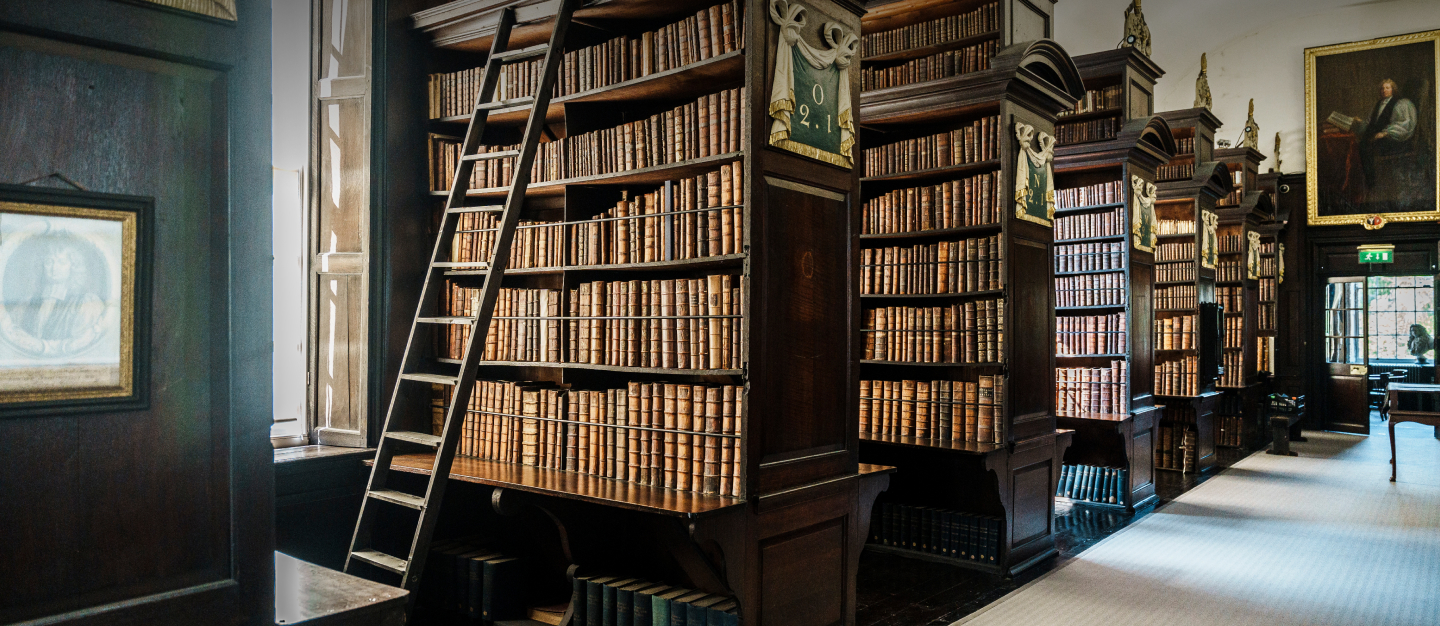

Some books have lived a long and adventurous life, having passed through many hands over the centuries. My research in Marsh’s Library – joint funded by the Consortium of European Research Libraries (CERL) and a Maddock Research Fellowship – aimed to piece together the exciting life of the Incunabula, books printed from 1450-1501.

Some books have lived a long and adventurous life, having passed through many hands over the centuries. My research in Marsh’s Library – joint funded by the Consortium of European Research Libraries (CERL) and a Maddock Research Fellowship – aimed to piece together the exciting life of the Incunabula, books printed from 1450-1501.

There are 77 incunables in Marsh’s Library. My main task was to catalogue them on the MEI (Material Evidence in Incunabula) database, which records copy-specific information such as owners, decoration and manuscript annotations.

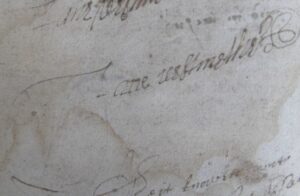

Signature of Jane Nugent, Countess of Westmeathe on ‘Fasciculus temporum’ (Lyon, c.1495)

Marsh’s volumes allowed me also to enrich the Owners of Incunabula database by creating 30 new records for renaissance book owners. Many owners remain anonymous, while others left their names. Among them are Lancelot Thexton, chaplain to King Edward VI and Jane Nugent, countess of Westmeath (d.1643), who survived her husband Richard Nugent, 1st Earl of Westmeath (1583-1642), only to see her lands attacked by the Catholic rebels during the Irish rebellion of 1641.

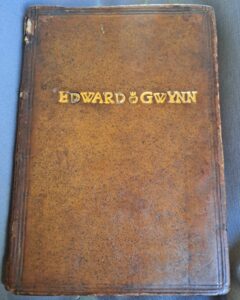

Edward Gwynn’s personalised binding

One of the most famous owners in the world of book-collecting was Edward Gwynn, immediately identifiable by the bindings bearing his name stamped in gold. The Library holds three of his incunables, one of which was not in the Folger Library’s list of all known surviving books from his collection, but has since been added.

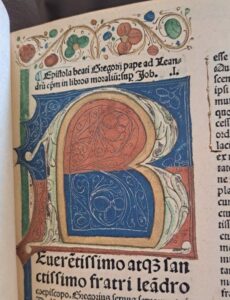

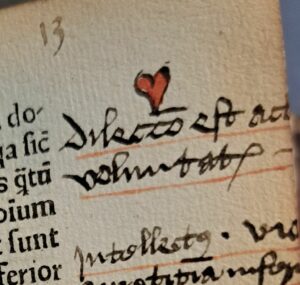

Marginal annotation on a book from 1482

But the true strength of these editions is to be found in the countless anonymous annotators who have read them time and again. Students took notes in the margins or between the lines of the text, monks highlighted passages of particular interest, commentators corrected some parts with words or even doodles, like human faces or little hearts. These reading marks are a precious source of information that tells us a great deal about how different people related to different texts.