Emily Lawless’ Story of Ireland

A photo of Emily Lawless left inside one of her books

Dr Renée Fox explores the archive of genre-defying Irish author and poet, Emily Lawless.

In the preface to her 1888 Story of Ireland, the Irish novelist and poet Emily Lawless (1845-1913) describes Irish history as ‘a long, dark road, with many blind alleys, many sudden turnings, many unaccountably crooked portions; a road which, if it has a few signposts to guide us, bristles with threatening notices, now upon the one side and now upon the other, the very ground underfoot being often full of unsuspected perils threatening to hurt the unwary.’ Described in these unexpectedly gothic terms, Lawless’s version of the Irish past refuses to follow a smooth, progressive narrative path from beginning to end. The narrative forms of Irish history, she concludes, will never have an endpoint.

‘The Story of Ireland’, 1888

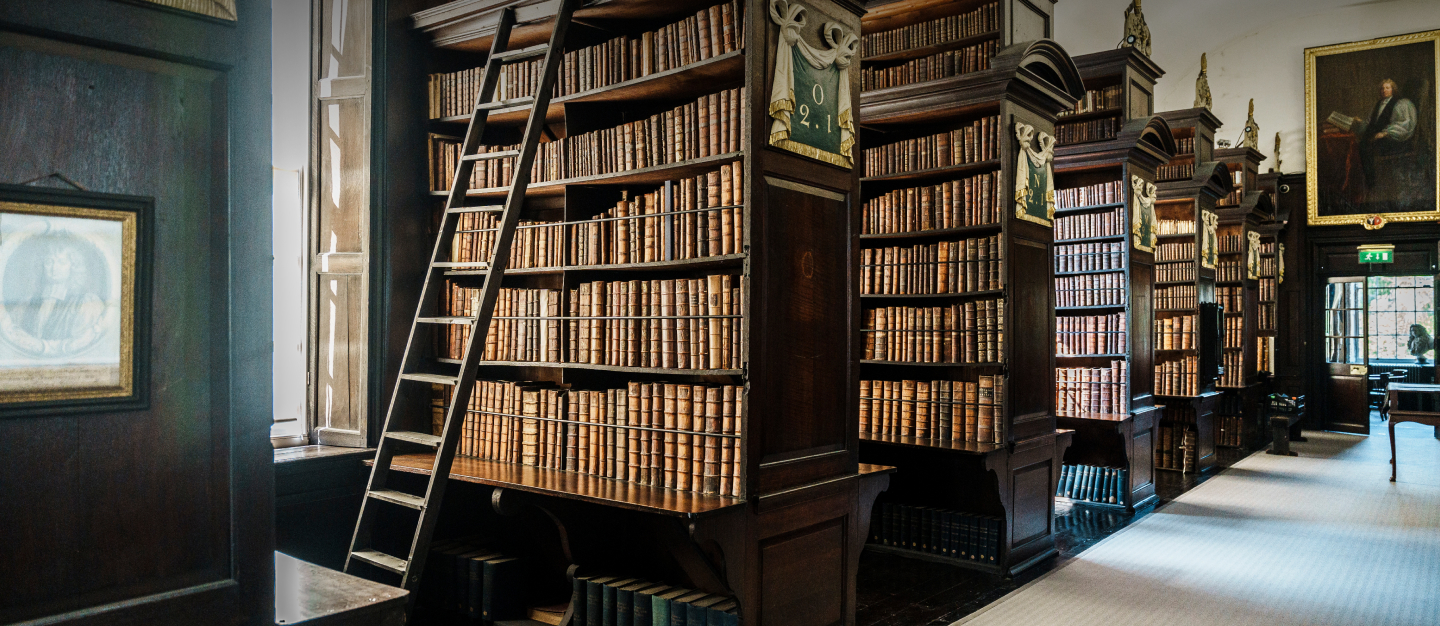

The second edition of Lawless’s Ireland, filled with newspaper cuttings detailing the honorary doctorate Trinity College Dublin conferred on the author in 1905, is part of a collection of Lawless’s books, scrapbooks, letters, drafts, and press cuttings that her brother Frederick donated to Marsh’s when he died in 1929. This collection offers a breathtaking glimpse of Lawless’s vibrant place in the late 19th– and early 20th-century British and Irish critical imagination.

I visited Marsh’s in May 2025 on a Maddock Fellowship to examine the Lawless papers and texts as I work on a new book called Violent Reading: Irish Novels and the Politics of Nineteenth-Century Genre. The book includes two chapters that explore how Lawless imagines the relationship between history, realism, and the gothic in The Story of Ireland as well as in novels like Grania: The Story of an Island (1892), Maelcho (1894), and The Race of Castlebar (1914).

Part of a review of ‘Maelcho’

My work in the collection was especially focused on how the press cuttings describe Lawless’s treatments of the Irish past, and I was searching for moments when critics comment on how she stretches and even creates/revolutionizes genre categories, or when they turn to the language of the gothic to make their points. For instance, in a Saturday Review article about the novel Maelcho, the critic insists that ‘Miss Lawless has produced something which is not strictly history, and is not strictly fiction, but nevertheless possesses both imaginative value and historical insight in a high degree. The genre itself is an original creation.’ Or, as another critic writes in a Manchester Carrier review of Ireland from 1888, ‘we are not brought to see the mere phantoms of the past passing in review before us. The power of a glowing imagination, of deep pity, of generous sentiments—the life-giving attributes of the writer’s own mind—have clothed them with flesh and blood.’

A drawing from Emily Lawless’ sketchbook

Focused as I expected to be on these kinds of critical reactions to Lawless’s prose, I was surprised on my last day at Marsh’s to find myself mesmerized by her final collection of poetry, titled The Inalienable Heritage and published posthumously after she died in 1914. These poems, as Lawless’s friend Edith Sichel writes in the preface to the book, ‘haunt the hearer with their poignant weariness, their waking nightmares’ as we encounter Lawless’s ‘struggle with bodily misery’ in her last year of life. Her final poem, ‘Aftermath,’ cries out for a poet who can sing Irish history to life for a new time, dark and perilous though it may be:

Out of the dusk of slow-accomplished Time,

Out of the shadows, out of the long past,

Lifting that past up on thy haughty rhyme,

Wakening those silenced voices, heard at last;

Fierce with the tumults of eight hundred years,

Loud with their cries of echoing strife and scorn;

Soft with their woes; child of their hopes and fears,

Poet we look-for, come; awake! Be born!

As Lawless is dying, her final call is for a new historical poet to be born, reminding us with her last words how inextricable her own history is from the unfinishable Irish history she spent her life imagining.

Dr Renée Fox, Associate Professor, Jordan-Stern Presidential Chair for Dickens and Nineteenth-Century Studies, University of California, Santa Cruz

Dr Renée Fox