How to insult your king

Kelley Glasgow

Recent Maddock fellow Kelley Glasgow explores how writing history in the 17th century provided an outlet to criticise the reigning monarch.

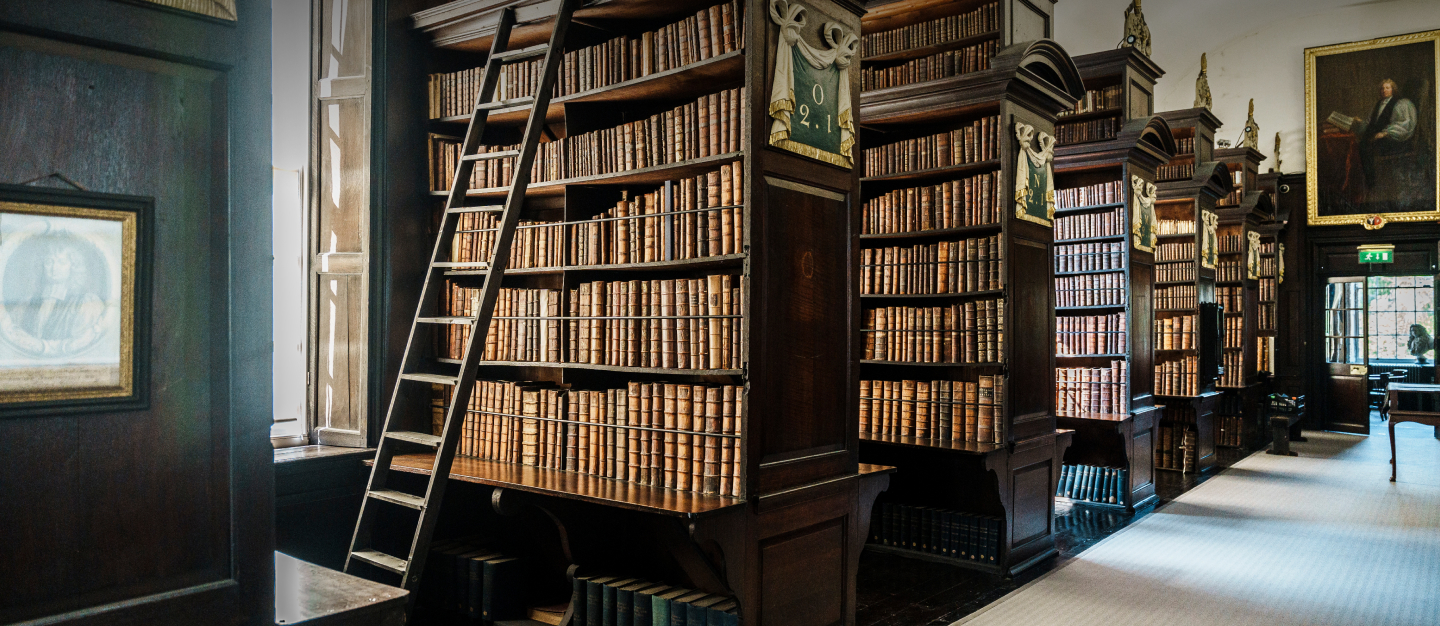

Marsh’s Library contains thousands of historical texts, many of which we might expect to be less than gripping reads. This is a fair assumption, given the massive compendiums of monarchical chronicles that populated medieval literature. In the late sixteenth century, however, these histories began to change in both genre and purpose. Shorter, more engaging works examined the inner lives of those who populated the past with the intent of evaluating those currently in power. If you were shopping for books in the early seventeenth century, you would see fewer giant chronicles and more ‘political histories’ that asked: is your monarch doing a good job compared to their predecessors?

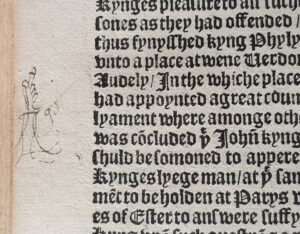

A manicule added by a reader to Fabyan’s Chronicle, 1516

During my fellowship in Marsh’s I examined many of these political histories. I was struck by the amount of opinions former owners felt compelled to add in their own hand. The library’s copy of Fabyan’s Newe Cronycles of Englande and of Fraunce (1516) is very heavily annotated by readers. One of the most delightful annotations was a scribbled hand, or manicule, pointing to a passage on the friction between King Phillip II of France and his barons, and King John who faced a similar situation in England. Though the chronicles were perhaps less pointed in their critiques, readers nevertheless found ways to insert their perspectives.

Engraving of Elizabeth I, from Fragmenta Regalia, 1642

The most cutting, derisive types of histories emerged in the early seventeenth century, as England began its long march toward the War of the Three Kingdoms in the 1640s. These political histories had a habit of comparing the Stuart monarchs, quite unfavourably, with the reigns of their ancestors. In the years preceding the war, Robert Naunton wrote Fragmenta Regalia OR observations on the Late Queen Elizabeth (1642). Naunton, describing the courtiers of the past, writes that ‘they were only favourites, not minions. Such as acted more by her own princely rules and judgements, then by their own wills and appetites, which she observed to the last’. It would be difficult not to apply this comment to the ruler in Naunton’s time, Charles I, and his unpopular counsellors. There was a proliferation of this type of historical material in the mid-seventeenth century, much of which was overtly political in a time when the very purpose of monarchy was under fire.

Insulting the king, even during wartime, was a delicate process. Censorship and arrests hung over the heads of those authors who went too far. But writing history, in the early modern period, was a convenient workaround for this problem. One could have plausible deniability with a statement akin to ‘Elizabeth I would never play favourites, like some do now’ or ‘political leaders used to make rational and informed decisions.’ The rise of these political histories and their rhetorical force for picking apart the English political system was a fascinating element of my visit to Marsh’s Library.

Kelley Glasgow, PhD student, Boston College