Sir Kenelm Digby, Pietro Bembo, and the contested origins of Italian

Maddock Research Fellow, Dr Niall Dilucia explores how annotations in Sir Kenelm Digby’s books reveal the diplomat & scientist’s interest in language.

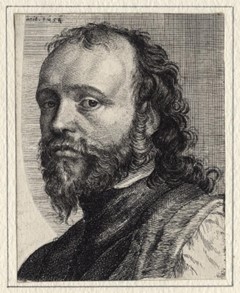

Sir Kenelm Digby by Richard Gaywood, after Sir Anthony van Dyck,1654, NPG D16450, © National Portrait Gallery

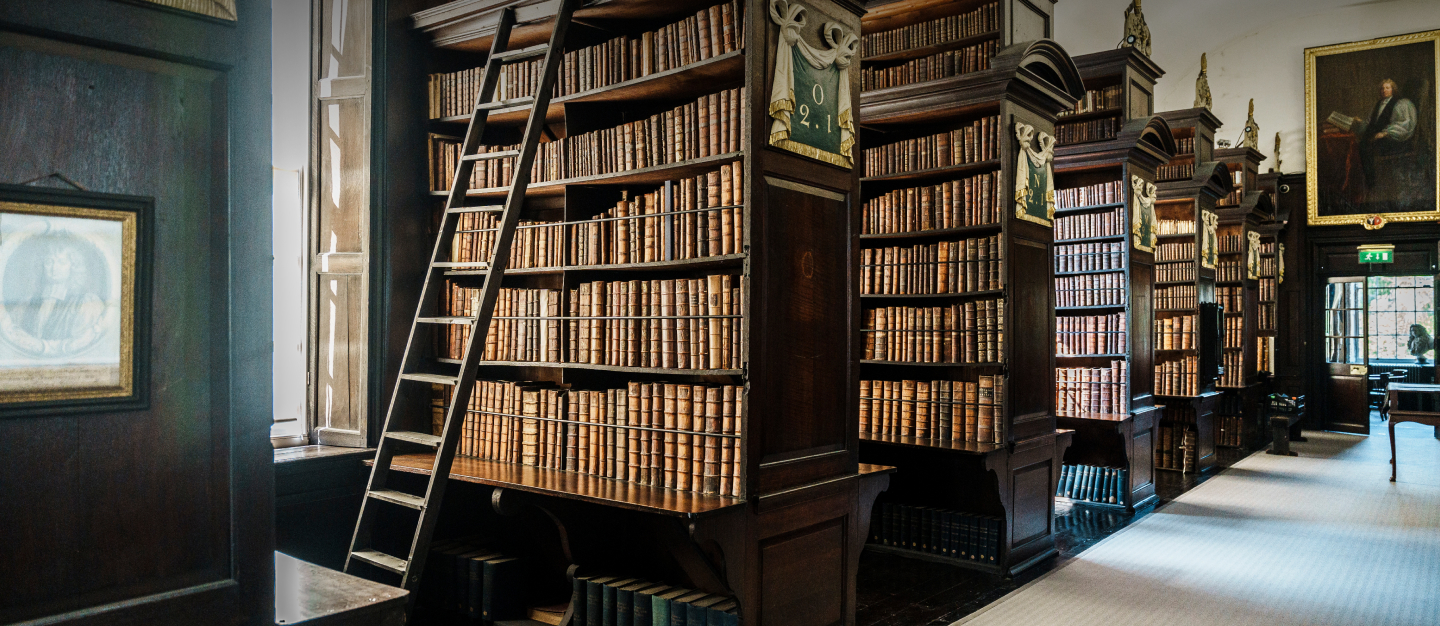

My time at Marsh’s Library was spent investigating the book collection of a seventeenth-century English Catholic philosopher, privateer, alchemist, and all-round bon vivant: Sir Kenelm Digby (1603–1665). Digby was an avid book collector, whose large library in Paris was broken up and sold after his death in 1665. Marsh’s is fortunate to have several books owned by Digby. Particularly special is a copy of the first edition of Pietro Bembo’s Prose della volgar lingua (1525) which contains numerous annotations by Digby.

In the Prose, Bembo champions the importance of vernacular Italian, and offers a highly influential investigation of its mechanics and history. Digby rarely annotated his books, and as such his copy of Bembo in Marsh’s is important for understanding his interests as a reader.

Annotations by Digby in his copy of Bembo, relating to Petrarch and Dante, the ‘lingua cortigiana’, and the Papal Court at Avignon

These annotations shed new light on his fascination with language and literature. In particular, they display Digby’s deep interest in the Renaissance debate over which Italian dialect is superior: the questione della lingua. For example, in one lengthy annotation on Bembo’s discussion of the debt owed by Tuscan to Provençal poetry, Digby notes that the great Tuscan medieval poets, Petrarch and Dante Aligheri sometimes used Provençal in their work. Leading on from this, Digby reminds himself of another example of the varied history of the Italian language. He writes that the dialect used at the Roman Papal Court at Avignon during the fourteenth century was called (‘detto’) lingua cortigiana, not Tuscan, and had multiple linguistic influences from across Europe. Digby clearly had opinions on the questione della lingua and understood something of the rich tapestry of dialects other than Tuscan that influenced the development of early modern Italian.

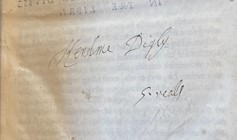

Title page of Digby’s copy of Bembo, with his signature and the price paid inscribed in his hand

The date of these annotations remains uncertain, but some clue might be provided by the recording of the price of the edition on the recto side of the title page. Written in Digby’s hand, underneath his name, is ‘50 reals’—the currency of early modern Spain.

We know with certainty that the Digby was in Spain in 1617–1619, where he was assisting the English ambassador to Spain, his relative John Digby, with the potential ‘Spanish Match’ of Prince Charles to the Infanta Maria Anna of Spain. Perhaps it was during these early travels, filled with youthful excitement, that the young philosopher purchased this copy of Bembo and dove headfirst into excavating the murky origins of Italian. In any case, Digby’s annotated copy of Bembo in Marsh’s collection reveals new information about the literary and linguistic fascinations of a seventeenth-century philosopher who remains best known for his scientific and philosophical ingenuity.

My thanks to Dr Ana Howie for a fruitful discussion of Digby’s Italian.

Niall Dilucia, Postdoctoral Fellow, CNRS and Maison Française d’Oxford