Paris O’Donnell talks about her recent research on our 15th century books

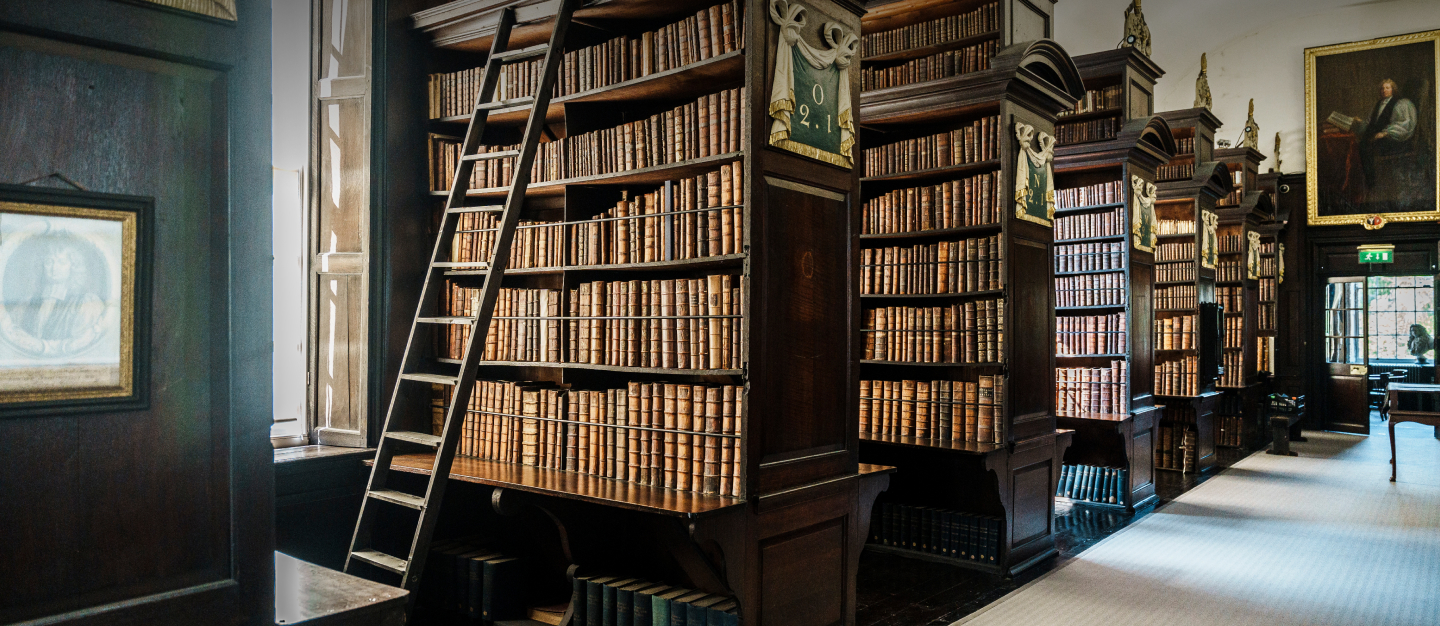

Marsh’s Library holds about 80 incunables (books printed before 1501). All of the Library’s fifteenth-century books necessarily travelled some distance to their current location, since the first book printed in Ireland did not appear until 1551. During my fellowship, I looked at each of these books to understand the routes by which they travelled into Marsh’s collections, and to identify the people who owned them along the way.

Many parts of the book yield clues about the journeys it made. The materials used in its binding and the rolls and stamps with which it is decorated can help us to associate it with particular points in time and space. For example, this binding by Garrett Godfrey, made distinctive by the gryphon, wivern and lion roll containing the binder’s initials, places the book in Cambridge in the second or third decade of the sixteenth century. It appears on this exceedingly rare copy of the 1493 Paris edition of Juvenal’s Satyres.

Another rich seam of clues about a book’s provenance are the ownership inscriptions, usually on endpapers or on the first leaf of the printed text. This edition of Juvenal contains numerous inscriptions by former owners, some more legible than others. If identified, these may help us fill in some parts of the route between early sixteenth-century Cambridge and early eighteenth-century Ireland, where its owner, Bishop John Stearne, bequeathed books to Marsh’s Library in 1745. Unfortunately, some of those who handled these books were not as positively disposed toward these inscriptions, and it is common to find them scribbled, rubbed or even cut out.

Turning every page of these very early printed books, I have found many annotations which comment on the text or help the reader navigate it on a subsequent reading. These can give useful insights into the reception and influence of a book. The style of the writing, the language of the annotations, the annotator’s references, even his or her spelling, can give us an insight that the book was read in a particular place, at a particular time, filling in some of the blanks in its provenance.

Most of these readers’ responses are written, but occasionally they are visual or graphical. This long-haired figure in a history of the Popes illustrates an episode in which Pope Anicetus reportedly decreed that no priest should wear his hair long. A few pages later, the annotator has drawn a latrine, illustrating the location in which, according to the text, Arius (who gave his name to the heretical doctrine of Arianism) came to a very messy end!

In contrast to the examples above, some of the markings in these books bear no relation to the text’s meaning or to their former owners. It is quite common to find letter practice, such as this alphabet, in a sixteenth-century hand, containing italic and secretary letter forms.

Paper was an expensive commodity, and the blank areas of a book’s margins or endpapers offered a precious space for writing practice. Sometimes just one or two letters were repeated over and over.

One reader left this long-necked bird in Nicolas Jensons’s 1475 printing of St. Augustine’s De Civitate Dei.

In some books there remains a catch of a song, or of a religious prayer or invocation, also seemingly unrelated to the text. In the following example, on an endpaper of Jacob of Voragine’s Legenda Aurea (Cologne, 1483), we find both. An early owner, Clement Vyllers, has claimed ownership in a hand typical of the late fifteenth century. He has also written the opening words in Latin of Psalm 62[63]: “Deus Deus meus ad te de luce vigilo”. He commingles the profane as well as the sacred, though, when on the next line he copies the beginning of a sixteenth-century English song lyric about a young girl seduced at court:

And I were a maiden,

As many one is,

I would not do amiss

When I was a wanton wench

Of twelve years of age,

These courtiers with their amours

They kindled my corage.

When I was come to

The age of fifteen year

In all this lond, neither free not bond,

Methought I had no peer.

What purpose these annotations served for Clement, and what connection, if any, they bear to the book in hand, remain to be determined. These questions might have been illuminated by the block of cancelled manuscript text, but that remains undeciphered and inaccessible.

Much of a volume’s former life leaves no physical mark, and the traces we do find may be illegible or indeterminate. If we are lucky, though – and attentive – they can plot a few precious points on the book’s route from the printing press to our hands.