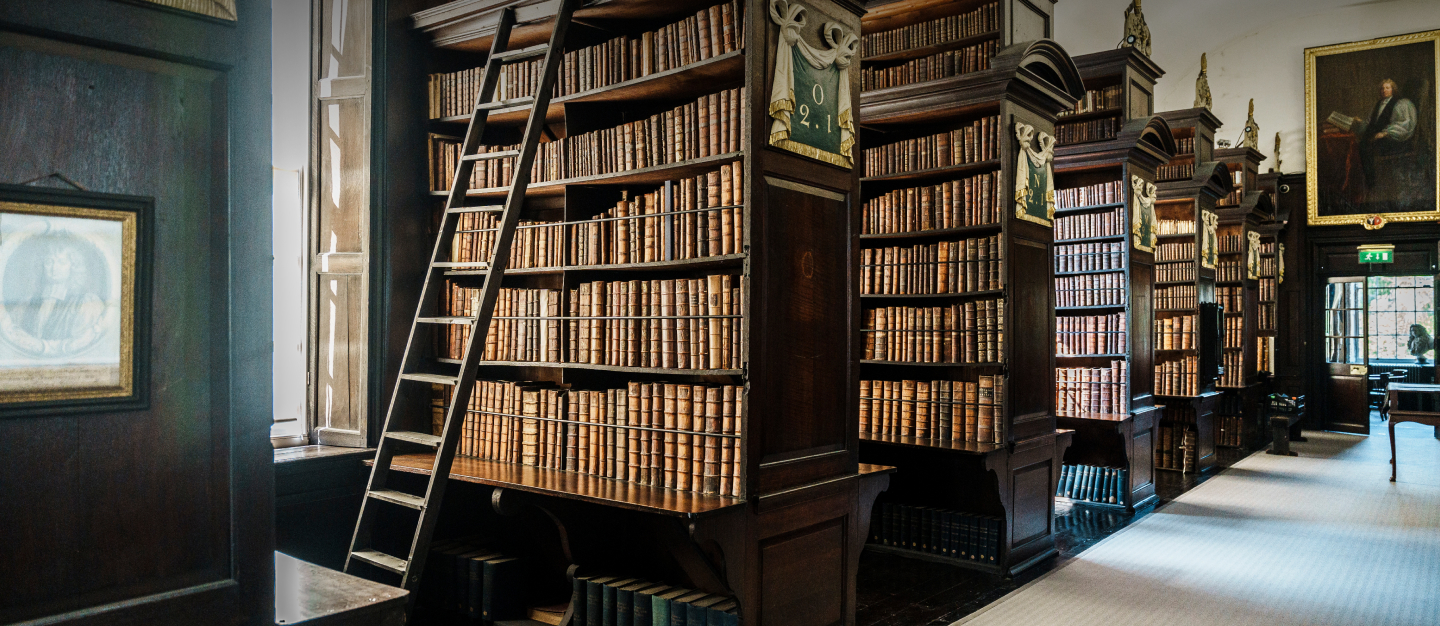

Recording injustice: Marsh’s rare French pamphlets

Maddock Fellow Dr Linda Briggs discusses the extremely rare French pamphlets she read during her recent Fellowship at Marsh’s.

I came to Marsh’s Library as a Maddock Research Fellow to investigate Huguenot lives in the early French Wars of Religion (1562–1567). This was a turbulent period in France. Disputes between Catholics and Huguenots, factionalism in the nobility and the inexperience of a young king all contributed to outbreaks of civilian and military violence. I hoped to find archival sources in Marsh’s Library that could shed light on how Huguenots experienced this conflict and how individuals and communities might have tried to prevent further instability.

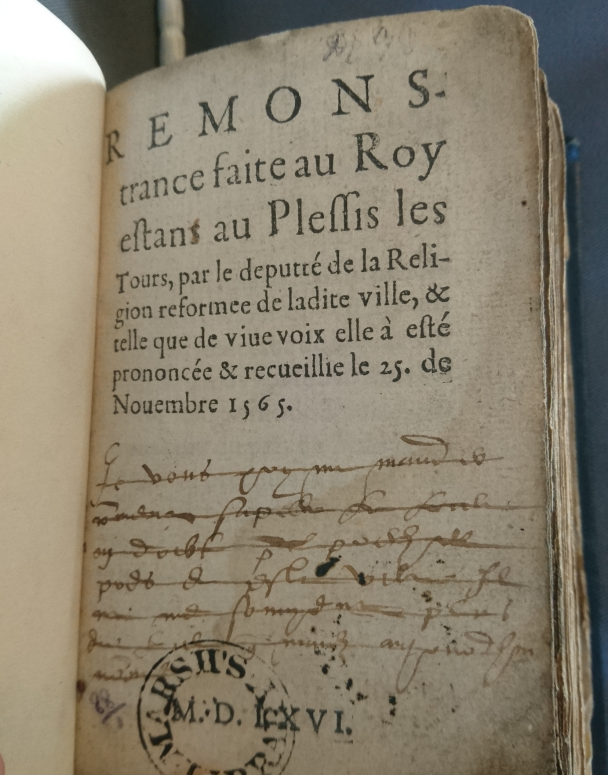

Pamphlet with inscription and Marsh’s Library stamp

Much of the material I read was in one sammelband (a single volume made up of individual documents bound together). Its contents were collected by Élie Bouhéreau (1643–1719), the first librarian at Marsh’s Library, who was himself a French Huguenot refugee. What was particularly remarkable about the volume was that it contained several rare and ‘sole survivor’ printed works. I knew that Marsh’s Library preserves hundreds of documents that were originally printed in batches and now survive as the world’s only copy. However, I didn’t expect to see so many in one binding.

Admiral Gaspard de Coligny

One of the most exciting unique copies was an account of the tribunal of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny (1519-1572), a leading Huguenot noble who was accused of orchestrating the assassination of a Catholic rival, Francis Duke of Guise (1519-1563). It proved to be fascinating reading, but frustrating too, because the first few pages were missing. What was written on these pages and is now lost? This document is a great example of how historians are always working from incomplete information to build a picture of the past.

Two further prints – a ‘sole survivor’ and a rare work that exists in only three copies – catalogued some of the injustices that Huguenots had endured since the outbreak of civil war in 1562. Together these documents indicated that many communities wanted the king to learn about their traumas, and to resolve hostilities between his subjects by exercising equity and justice.

I was fortunate to read several sources in Marsh’s Library that have the potential to shape my research. Just as valuable to me, though, was the experience of unexpectedly encountering so many rare printed works. It was a thrill and a privilege to be able to handle them and to find out first-hand what a remarkable collection is held in Marsh’s Library.