Tales of Whales

Maddock Fellow Dr Corrina Readioff describes how our attitudes to whales and marine life has developed over the past 500 years.

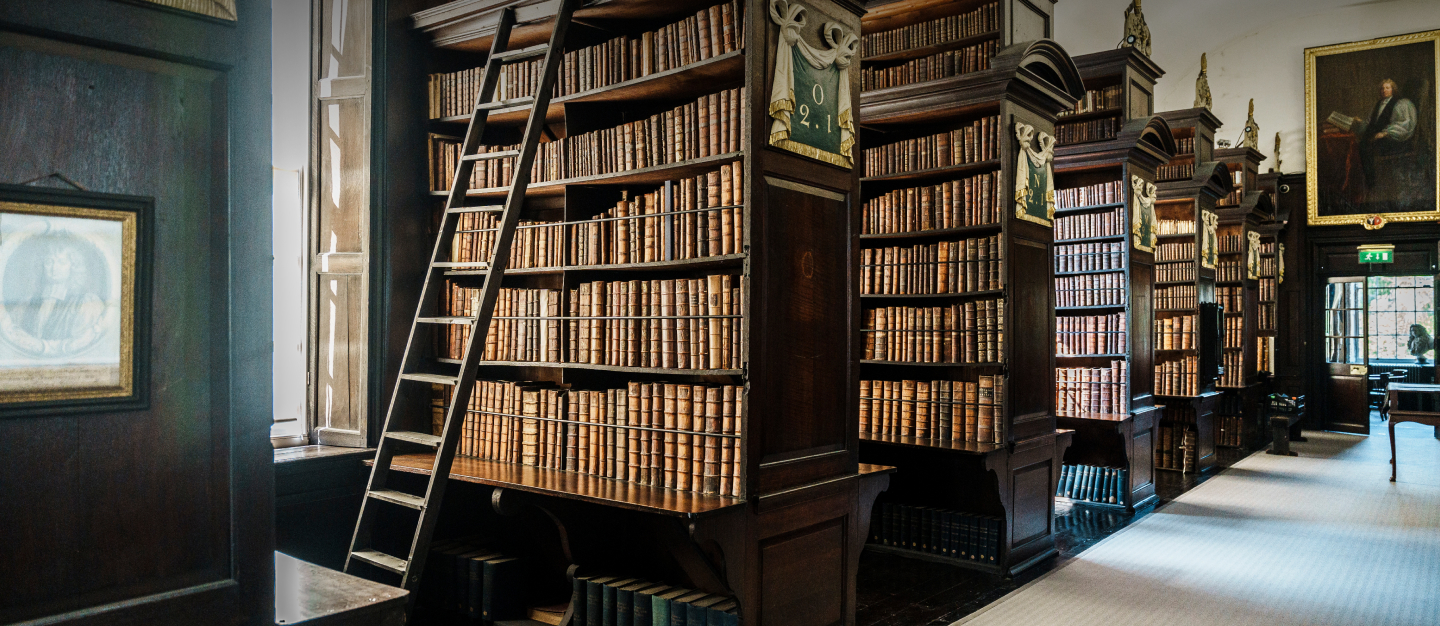

Olaus Magnus’ Carta Marina, in Antoine Lafreri’s Geografia Tavole, c.1560s.

As the largest creatures ever to have lived on our planet – larger even than dinosaurs – whales have long held a unique place in the popular imagination. I am interested in how early modern literary and cultural perceptions of whales have shaped modern day attitudes towards cetaceans and the marine environment. During my Maddock Fellowship at Marsh’s, I was able to study a wide range of whale-related material from the time, from natural history texts and pharmaceutical guides to political philosophy and maps.

The early modern period was a critical turning point in Western attitudes towards marine life, when traditional perceptions of whales as devilish metaphors or omens of death collided with a rising demand for whale oil and whalebone to power industrial development. While the emergent European whaling industry seized upon the commercial potential of products derived from whales, there remained comparatively little public awareness in the Western world of what a whale actually looked like.

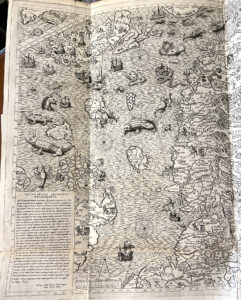

Detail of sea monsters from the Carta Marina, including the whale attacked by an orca.

A particular highlight of my visit to Marsh’s was the opportunity to see and study a copy of Antonio Lafreri’s 1572 reproduction of Olaus Magnus’s influential Carta Marina (originally published in 1539). Lafreri had included the map in his Geografia Tavole moderne di Geografia, a text widely considered to be the first attempt at producing an atlas of the world (or at least the world as it was known to Europeans).

Magnus filled his ocean with scenes relating to the stories he had collected of life in and around the Northern seas. Some of these now appear fanciful, such as the sea serpent, or the whale mistaken for an island; but others have a solid basis in fact, for example the unicorn-faced narwhals or the suckling whale harassed by an attacking orca or killer whale. Magnus’s map, together with his Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (History of the Northern Peoples) (1555) which provided an extensive textual commentary on the scenes and nations depicted, became a key reference point for later geographical and natural history texts, with both text and images quoted and copied.

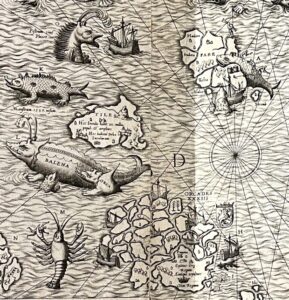

Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia Universalis (1554) which I was also lucky enough to see at Marsh’s Library, included an engraving in which the sea creatures from Magnus’s map were copied and rearranged into a single image depicting ‘Monstra marina & terrestria’: monsters of the ocean and land. My research will place these images and text within a wider context of whale-related literature from this period, exploring how emergent scientific and commercial interests blended with the whale’s traditionally monstrous portrayal.

Dr Corrina Readioff, University of Liverpool

‘Monstra marina & terrestria’ from Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia Universalis, 1554.