Murder at the French Court

Dr Una McIlvenna explores the the secret murder of Concino Concini, adviser to Marie de Médici, and the French crown’s subsequent pamphlet campaign to blacken his name.

Portrait of Concino Concini, maréchal d’Ancre (c.1575-1617) by Daniel Dumonstier, from the collections of the Musée du Louvre (via Wikipedia)

In Paris on 24 April 1617, guardsmen loyal to the young French king Louis XIII shot at close range the chief adviser to the king’s mother, murdering him in cold blood. Concino Concini, maréchal d’Ancre, was an Italian politician who, along with his wife, Léonora Galigaï, were favourites of the queen mother Marie de Médicis. The couple’s meteoric rise to power made them loathed figures in France.

After Cocini’s murder, the king’s guards discreetly buried his body, but when the Parisian populace found out what had happened, they dug up his corpse, dragged it around the city, and then hanged, mutilated, and burned it. This mutilation and destruction of the corpse was followed in the next few months with a veritable explosion of pamphlet material attacking the Concini couple and celebrating their deaths.

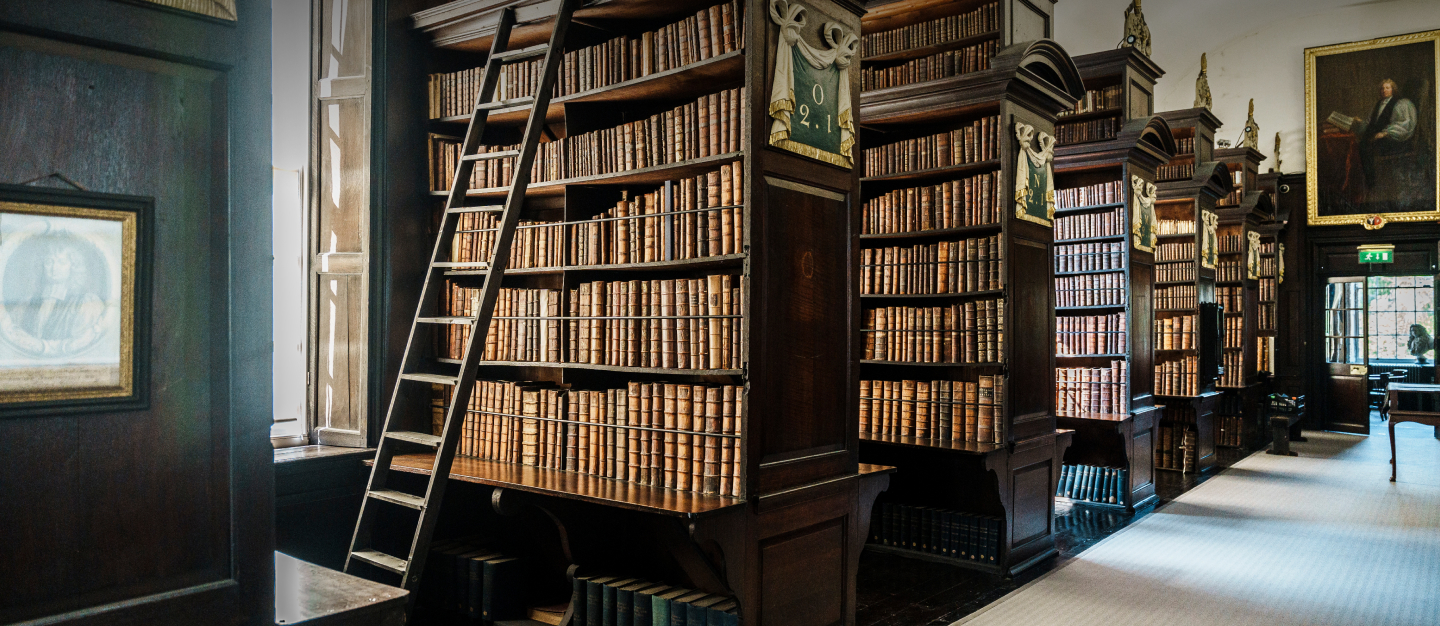

I visited Marsh’s Library in May 2023 as a Maddock Fellow to explore its extraordinary collections of material related to this pamphlet campaign. I’ve also had the chance to document collections of related material in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, and the Newberry Library in Chicago, and now I’m in the position to compare hundreds of pamphlets, all produced in a brief window in 1617.

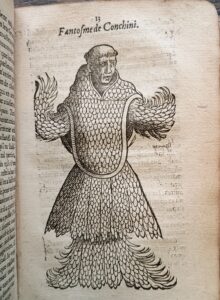

The ghost of Concini, from Dialogue de la Galligaya et de Misoquin … (Paris, 1617)

It seems clear to me that there was a concerted propaganda campaign by the French Crown to control the narrative of the shocking events. There were all kinds of awkward questions raised by what happened: if Concini was trying to usurp the throne, as his critics said, then that could reveal too much about royal favouritism; if he was really a terrible criminal then why wasn’t he put on trial and executed properly instead of a secret assassination?

The variety of genres in the collection is dizzying: prose pamphlets, Latin verse, songs, anagrams, acrostics, and even a play (which I have a feeling is probably terrible). There is also material in multiple languages: as well as French and Latin we find English, German, Italian, and Dutch. And there are all kinds of images; in Dialogue de la Galligaya et de Misoquin esprit follet, qui luy ameine son mary Concini is depicted as a monstrous ghost, with scales and feathers.

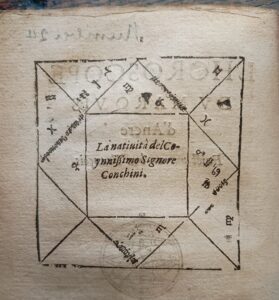

Concini’s horoscope, from L’Horoscope du Marquis d’Ancre faict par un bon François (Paris, 1617)

The Horoscope of the Marquis d’Ancre includes what looks like a horoscope reading of Concini’s stars, but which I’ve been reliably informed is just nonsense, created to look like the real thing, and to convince readers that he was cursed from birth.

So why the incredible diversity of genres, languages, and forms? Why not just print a few prose pamphlets and be done with it? My theory is that the Crown knew it had to reach as many people as possible and so printed material in every possible genre to reach everyone, no matter their literacy, education, language, or income. I’ll be more confident about my theories once I’ve managed to get through it all, which will be no mean feat! But I am extremely grateful to the Marsh Library and the Maddock family for granting me this fellowship and allowing me to tell the story of a truly remarkable moment in French history.

Dr Una McIlvenna, Senior Lecturer, English College of Arts & Social Sciences, Australian National University

Dr Una McIlvenna