Willem Piso and the wonders of Brazil

Research Fellow Timothy Dale Walker describes Piso’s publication on Brazilian flora and fauna

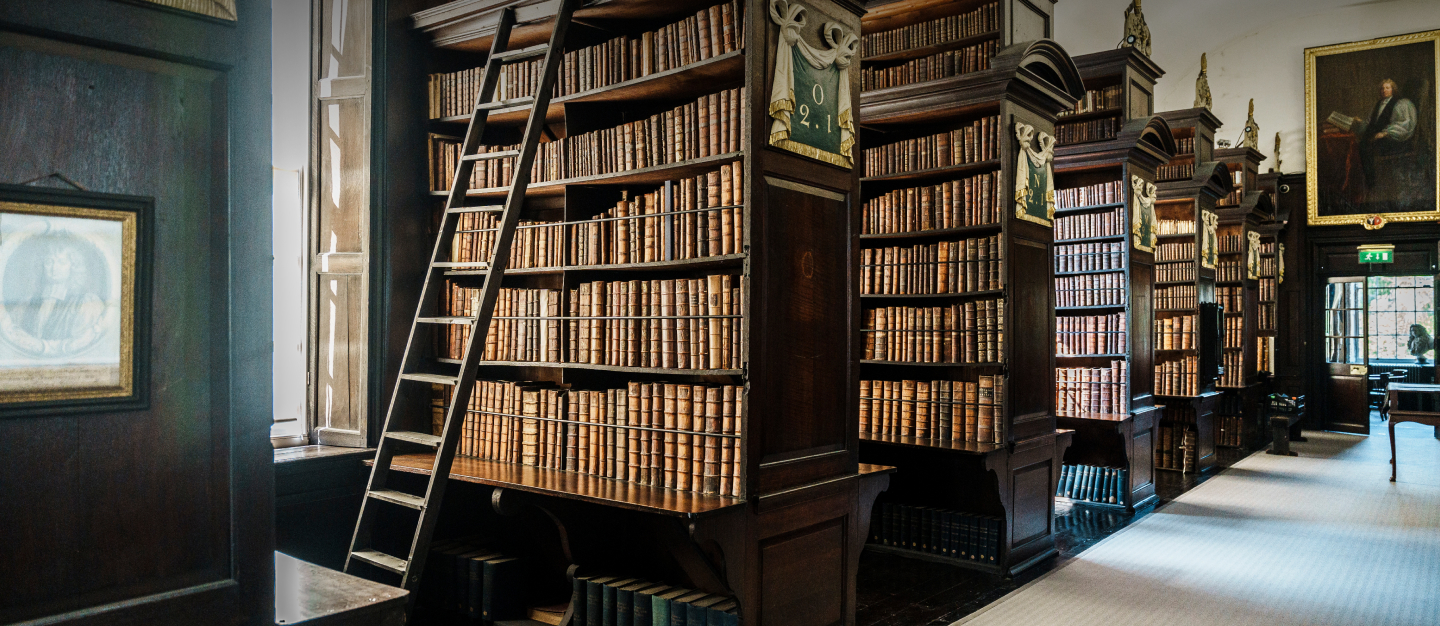

One of the exceptional early modern medical books held in the collections of Archbishop Marsh’s Library is a groundbreaking seventeenth-century work that described Brazilian flora and fauna. As a Library Fellow, my research project was designed to answer this question: “When did northern Europeans begin to absorb lessons about medicinal substances from the Portuguese colonial sphere — Brazil, Goa or Macau — into their day-to-day medical practice?” The publication in question, produced in the Netherlands, dealt specifically with the medical benefits that could be derived by applying healing plants from the Amazon and other parts of Brazil.

Competitive Dutch and Portuguese colonial/imperial ambitions collided in Brazil in the seventeenth century, with significant ramifications for European botanical and medical knowledge. Dutch attempts to conquer and occupy parts of the Brazilian coastline (1624-1654) in the hope of exploiting the colony’s rich sugar producing regions also resulted in a brilliant new treatise of ethno-pharmacology.

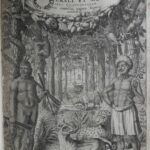

Historia Naturalis Brasiliae, published in Amsterdam in 1648, was the work of three authors, all trained physicians: Willem Piso — who had been the personal physician of Johan Maurits of Nassau (governor of Dutch Brazil, to whom the work is dedicated) — Georg Marcgraf, and Johannes de Laet. With its beautiful, accurate engraved images of plant and animal life, Historia Naturalis Brasiliae represents the first comprehensive natural history of South America.

Willem Piso in particular distinguished himself as an investigative medical pioneer, and became one of the earliest northern European authorities on tropical medicine. He contributed four ‘books’ (chapters) with medical themes to Historia Naturalis Brasiliae, contained in a section entitled De medicina Brasiliense. These chapters include detailed descriptions of endemic regional diseases and the plant-based remedies Native Americans used to treat them. Piso wrote one discrete section of the work devoted entirely to medicinal plants, and another focusing on venoms, venomous animals and native antidotes.

A decade later, in 1658, Piso published a new edition of Historia Naturalis Brasiliaeunder his name alone. The revised version ran to

fourteen volumes and included dramatically expanded observations on Brazilian remedies. Piso introduced northern Europe to many of the unique Brazilian medicinal plants (ipecacuanha, copaíba, jalapa) and indigenous healing methods long known to Iberian

missionaries and colonists in South America. Piso’s achievement far outshone the Portuguese for detail, clarity and scientific method. Ironically, though Historia Naturalis Brasiliae significantly furthered the dissemination of plant remedies and healing knowledge from Brazil to northern Europe, its success had little impact on continental Portugal. As the work of a Protestant empiricist physician from a nation with which the Portuguese were at war, Piso’s masterpiece was banned by the Portuguese Inquisition’s Board of Censorship. Hence, Piso’s work remained virtually unknown in the Lusophone world until the later nineteenth century – by which time this knowledge had been available in Ireland for nearly 200 years.

The version held in Marsh’s Library, Willem (“Gulielmus”) Piso’s De Indiae Utriusque Re Naturali Et Medica Libri Quatuordecim (Amsterdam, 1658), appears to be a single-volume abridged version of the works described above, bound together with additional medical material from colleagues Georg Marcgraf and Jacob Bontius. There are two copies of this work in the library, one in the collection of Edward Stillingfleet, bishop, controversialist and correspondent of John Locke among others; and one in the collection of the first librarian of Marsh’s, the Huguenot Elie Bouhéreau, who was both cleric and practising medic.

- Cuandu (Coendou prehensilis), a tree porcupine

- Erva-de-Santa-Maria, a vermifuge

- Chili peppers in glorious variety!

- A hummingbird described as ‘most beautiful’

- The emetic ipecacuana

- One of several varieties of passion flower shown in Piso’s treatise

- The title page of the copy from Stillingfleet’s collection

- A mosquito whose tail curves like a scorpion

- Timothy Dale Walker in the Azores Archive (UMass)